Why the silence on water infrastructure?

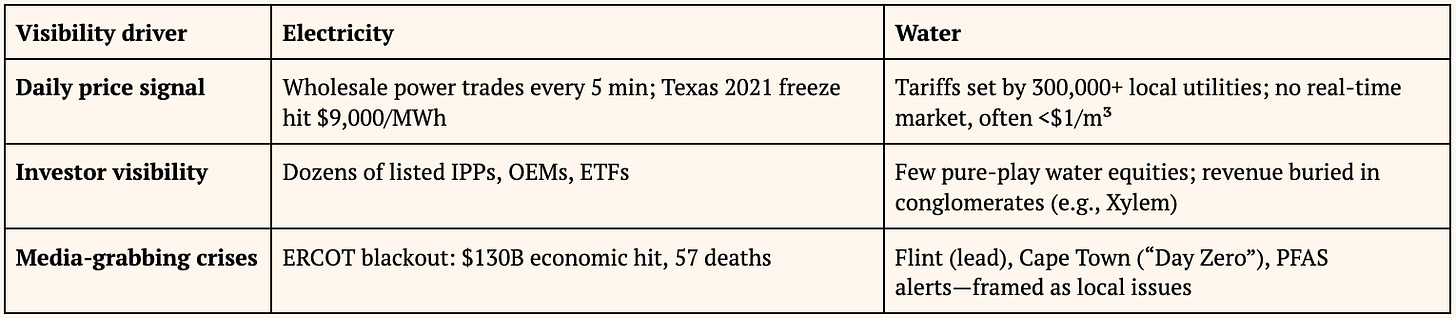

Why does electricity dominate headlines and capital flows, while water, arguably more essential, remains overlooked?

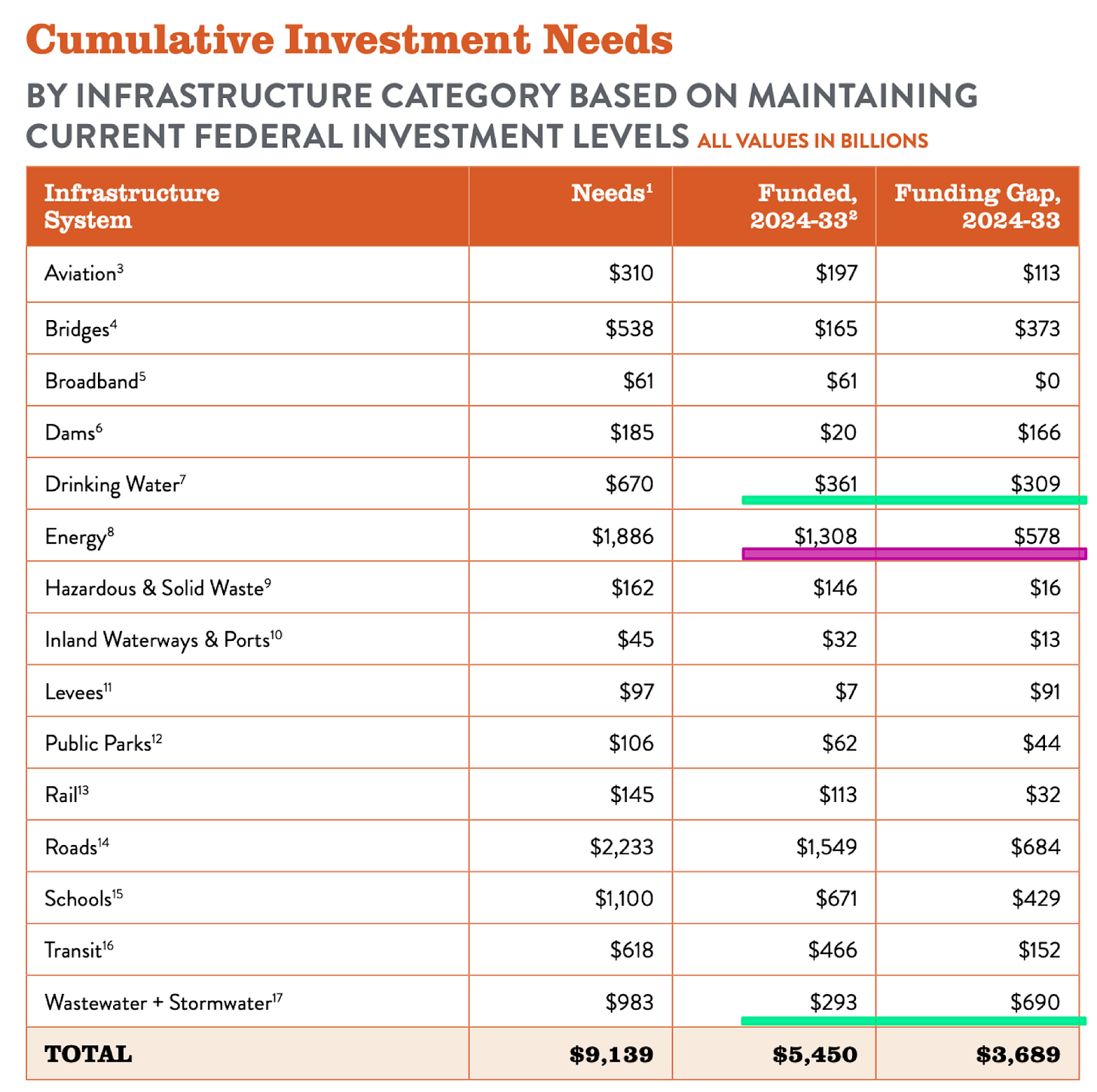

Despite being just as foundational to modern life, water infrastructure attracts a fraction of the attention and investment. The global funding gap is estimated to reach $7 trillion by 2030 (World Bank), with $900 billion required in the U.S. alone, as shown in the table below.

Is there a relationship between the rate of innovation and how critical something is?

You need to be critical for the market to care, but not so critical that it feels paralyzed by the risk of disruption. Innovation is also constrained by the nature of water itself: as a life-critical system, it demands high reliability and has zero tolerance for failure. You can’t A/B test a treatment system the way you might a battery or a vehicle. That makes buyers, especially utilities, extremely risk-averse and leaves little room for experimental technologies to scale without years of validation.

Another challenge is that water isn’t priced, traded, or tracked in the same way as electricity. Electricity has centralized markets, daily price signals, and investor visibility. Water management, by contrast, is very localized, with more than 300,000 public utilities worldwide. Tariffs are often politically capped, with no real-time price screen, and in many regions, water is priced below the cost of delivery. (I’m not suggesting increasing water prices. Price increases do not always work given the public utility).

Just as electricity access was expanded and improved by modernizing generation and delivery systems, water infrastructure requires modernization. The opportunity isn’t to make water more expensive; the opportunity lies in making it safer, more reliable, sustainable, and future-proof. That’s what we are learning and exploring at Transition. We’ve been interested in water for a while; we partnered with Waterplan, but we are still developing our thesis in the space. Now, we’re exploring the physical infrastructure opportunity, especially on the industrial side. What follows are a few thoughts:

The State of the Market and Tech today

Water demand could be categorized as follows:

Municipal Utilities: the largest share of the market by volume. Utilities are the central node through which most water is sourced, treated, and distributed to residents, businesses, and many industrial users. They draw from surface water, groundwater, or desalinated seawater, treat it in centralized plants, and manage delivery and discharge. Some large industrial users may draw directly from groundwater or surface sources, but most remain tied into utility networks for either intake, discharge, or backup supply.

These entities are under pressure to upgrade aging infrastructure, which was largely built before today’s contaminants (e.g., PFAS, microplastics, lithium) were even understood. Yet their budgets are tight, and political constraints often limit rate hikes. Public procurement cycles and low risk tolerance make it difficult for new tech to break through. Most utilities are structurally incentivized to pursue incremental upgrades over full-stack modernization. As a result, they bolt on new solutions to aging systems: starting with heavy metals, now layering in PFAS treatment. They tend to prefer to do that over even better rip-and-replace solutions. The typical utility tech stack can involve 8–12 sequential treatment steps, each adding complexity and cost.

Commercial and Industrial: This sector accounts for 80% of water use (whether directly or from utilities). They face varying contamination profiles, purity targets, discharge requirements (Restaurants, offices, labs, hotels, manufacturers, farms – they are not all the same). Even if these sectors withdraw from utilities, they still have to interact with water treatment systems at the intake and discharge points.

First, water serves as an input regardless of its source, often requiring additional on-site treatment on the inlet side to meet operational standards, especially in sectors like semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, food and beverage, and advanced manufacturing.

Second, water is also an output. These users treat wastewater before discharge, either to comply with environmental regulations, reduce disposal fees, or enable recycling and reuse. Many are adopting systems that recover more usable water from their waste streams, reducing both cost and resource dependency.

Residential: Although residential water quality is not the primary focus of this piece, it serves as an important behavioral indicator of trust in public systems, and public opinion can serve to influence public utility behavior (such as the demand to remove PFAS from drinking water).

Even in cities with safe municipal water, more than 54% of Londoners still filter their tap water, driven by concerns over taste or fears of lead and PFAS.

—

Water technologies to process and meet that demand are supplied by a few players (DuPont, Toray, LG Chem, Veolia, Xylem, Pentair) who dominate membranes, chemicals, and integration. A lot has been written about those companies, so I won’t elaborate here. But what stood out to me, reading their 10-K and other reports:

Many of those players are diversified corporations where water-related products and services constitute only a portion of their overall business. For example, DuPont, which has a 22% market share in RO, generates only 11% of its revenue from water-related products. This diversification often results in limited investment and innovation in water-specific technologies, as it doesn’t directly relate to the company’s survival. Of the major players in the water industry, only Xylem (~33% market share in water equipment) focuses entirely on water technologies.

R&D investment in water treatment companies is significantly lower than in other technology and industrial sectors, with figures ranging from 0.28% of revenue (Veolia) to 4.2% (DuPont and LG Chem). Even Xylem, with an entirely water-focused portfolio, invests 2-3% of revenue into R&D. This contrasts sharply with sectors like software (7.5% at Netflix to 28% at Meta), pharmaceuticals (17% at Pfizer to 24.4% at Eli Lilly), and semiconductors (8% at TSMC to 30% at Intel). Additionally, water infrastructure patenting (1.3 million patents) is less than half of electrical inventions (3.1 million) over the past decade, indicating a clear lack of translatable research and innovation in the water sector.

Even as these same firms face billions in PFAS liabilities (DuPont’s $1.19 billion+ settlement), few have delivered scalable solutions for destroying PFAS, despite plenty of ongoing research on the topic. It’s a symptom of the same issue: water is buried in portfolios, not owned by leadership. Why haven’t they deployed large-scale solutions that would save them from these liabilities?

At the intersection of the demand and supply mentioned above, there sits a brittle and outdated delivery system that is inflexible to population growth:

Aging pipes and leakage: 60 million gallons of water are lost every year due to pipe failures and leakage. And nearly 19.5% of treated drinking water in the U.S. is lost before it reaches customers or is improperly billed.

PFAS and emerging contaminants: New EPA rules set maximum contaminant levels at 4 ppt for PFAS chemicals. Most utilities lack the equipment to detect or treat them. Estimated upgrade need: tens of billions over the next 5 years.

Reuse and high-recovery treatment: Industrial facilities and water-scarce cities are pushing for wastewater reuse. But most reverse osmosis systems still waste 40–50% of water as brine. Opportunity: high-recovery membranes, CCRO systems, brine concentrators.

Resource recovery: Wastewater contains valuable nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus) and sometimes trace metals (e.g., lithium from geothermal brines). Most of this is currently discharged.

Underserved communities and off-grid users: Over 2 million Americans lack access to safe drinking water. Rural and tribal systems often face high per-capita costs and limited technical support.

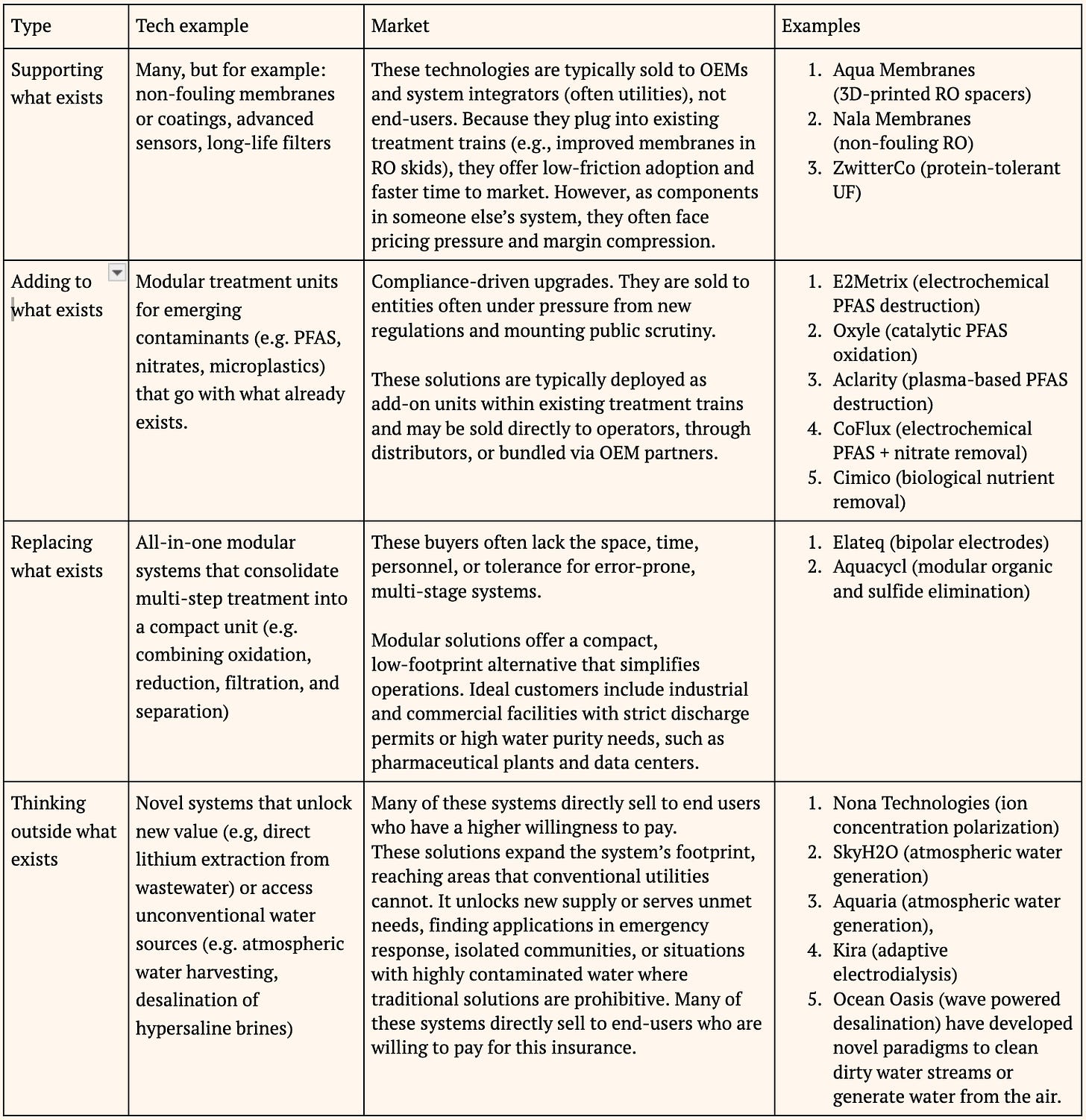

We see four areas for innovation:

These challenges and the urgency for solutions can be an opportunity for attractive investments. Innovations in water could take many forms. Here are some of the categories as we view them:

We will continue to explore all of these areas, but we are particularly interested in the middle two: “adding to what exists” and “replacing what exists.” These approaches balance ambition with feasibility. They address urgent needs (like PFAS destruction or high-purity reuse). They unlock new access. They can be adopted without overhauling entire systems, creating paths for near-term impact and faster commercialization.

Water is one of the most essential systems in our modern world, but one of the least visible. The challenges are immense, but so are the opportunities to rethink how we source, treat, and reuse water at every scale.

If you’re a founder, scientist, operator, or expert advancing water solutions, we’d value the chance to exchange ideas. Please reach out.